Cape Cod Canal History

The canal, a man-made structure, epitomizes the region that it separates from the rest of the state. Part of what makes the canal so special is its connection to the people that cross paths with this body of water on a daily, weekly, monthly and annual basis.

Perhaps no one is more familiar with the canal and its past than Bourne Selectmen Donald (Jerry) Ellis who spends his days as the superintendent of the Sagamore Cemetery, one of the most haunted places in all of Cape Cod. To find out why, one has to go back to 1909 when there was not even a canal.

By that time, the planning and preparation to build a cut-through of Cape Cod was well underway and in June of that year the first shovels were planted in the ground by the project’s financier August Belmont II to ceremoniously kick-start the massive undertaking.

In order for the project to be successful, there had to be major changes to the Cape’s landscape. Chief among those was the relocation of 17 bodies buried in the Bourne Cemetery and 45 bodies buried in the Emory Ellis Cemetery as both plots stood directly in the path where the canal was to be built.

The move was not looked upon kindly by Emory Ellis who stopped the building of the canal in 1909 “because he wanted a choice spot in the Sagamore Cemetery to move his family members to,” Donald Ellis said. “So when it came time to move everything, he sat in front of the cemetery with a shotgun and wouldn’t let anyone touch anything until he was satisfied his family got the right spot in the Sagamore Cemetery. He was an ornery obstructionist and a typical old Yankee, but he got what he wanted.”

Or did he? When it came time to finally find the bodies there was a problem. The coffins were not properly aligned with the gravestones, leading to what Mr. Ellis believes are some troubled spirits that haunt the Sagamore Cemetery.

It has made the cemetery, located roughly 200 yards from the canal, a popular locale for those interested in the paranormal. During his time caring for the grounds and its deceased inhabitants, Mr. Ellis said, he has reported eerie sensations—goose bumps, hair standing on the end of his arms, the smell of pungent cigar smoke and an intense pressure on his chest—that are indicative of a ghostly presence.

A different kind of horror is felt by those who travel across the canal in the summertime. While traffic backups may seem like a modern ordeal, Mr. Ellis said, they are not. “When they were building Camp Edwards in 1939, the bridges were so jammed from Wareham to [the base] they had to create a system of one-way traffic from 5 to 8 am over the bridge and then in evening it was one-way going back,” he said. “The traffic patterns and back-ups are nothing new to anyone. Outsiders get upset with it, but we live with it.”

While ghosts and traffic represent the downsides to the canal, Mr. Ellis still had high praise for the engineering marvel. “It draws a huge amount of tourists which our whole economy on Cape Cod is based on,” he said. “This is probably one of the greatest amenities you can have.”

Fellow Bourne resident Skip Barlow, president of the town’s historical society, agreed. As owner of Barlow’s Clam Shack across from the canal rest area in Bournedale, he sees firsthand the tourists who take advantage of “the biggest free recreation area in Southeastern Massachusetts.”

These are people who take to the canal to walk, rollerblade, bike, fish and sunbathe. “The canal is used year round by tourists and locals alike,” he said. “About three million people use it for recreational purposes annually… It’s kind of a neat place and it’s free and easily accessible.”

Not only is the canal a great place to people watch, he said, it is a prime spot for boating enthusiasts. “You can see almost any kind of boat go through there at any time of year,” Barlow said. “It is pretty cool if you like boats. I’m right out there checking it out because I really enjoy those things.”

Among the more prominent boaters to travel through the canal were Phil Donahue and his wife Marlo Thomas in the 1990’s. “I was shocked by the size of their boat,” Bob King, the co-owner of Café Chew in Sandwich, recalled. “He drove it by himself. It was just him and Marlo. I asked him, ‘You can handle this by yourself?’ and he said, ‘Oh yeah.’ It was huge.”

King and his husband and business partner Tobin Wirt were invited onto the yacht which had been tied up for the evening at the Sandwich Boat Basin, adjacent to the canal. Just a few hours earlier Donahue and Thomas had dined at the Bee-hive Tavern, a Sandwich eatery that King and Wirt owned from 1992 to 2004.

“After they had dinner of course they needed to get back to the boat and they asked if we could call them a taxi,” King said. “There were no taxis at the time so we offered to give them a ride. We gave them a nice tour of Sandwich… They enjoyed that. When we got to the boat they invited us on.”

King’s other vivid memory of the canal was from his childhood when his father, an avid fisherman, would “terrify us about falling into the canal and that it would swallow you up. We couldn’t even put our toe into the water. He was afraid of the current.”

Though illegal now, at one point taking a dip in the canal was commonplace, even after the Army Corps of Engineers took over control of the waterway in 1928. “We used to go swimming in it all the time,” said Wally Alden, who grew up in Sagamore and now lives in Buzzards Bay.

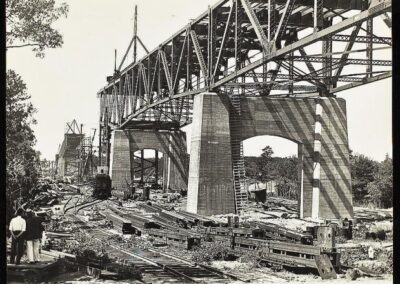

His connection to the canal extends to his father William Alden and his uncle Burton Alden who both worked on the construction of the Sagamore Bridge which opened to traffic in 1935.

As a child, he remembered days when his father would pile his family into his Buick and drive them up to the bank of the canal to watch the boats come by. From a purely practical point of view, he noted that the canal has been beneficial for boats by cutting off the travel time it takes to go around Cape Cod.

But to him, the canal is more than a utilitarian object. It is a place where he used to catch tautog, cod and flounder as a child. Now he passes on these family traditions to his 18 grandchildren and 12 great grandchildren who visit from as far away as Florida and Texas. “We take them along the canal and they just love to sit there and watch the railroad bridge go up and down,” he said. “They are really fascinated by it.”

The public’s fascination with the canal extends far beyond Cape Cod. “Whenever we travel and wherever we go, we tell people we live in the town before the canal,” Wareham’s Claire Smith said. “I use it as a reference because people seem to know it wherever you go.”

She too was drawn to the popular landmark at a young age. On an occasional Sunday—when she and her older sister Patricia were supposed to be in church, the pair would drive down to the canal and watch the boats pass through. “We were sworn to secrecy,” Smith laughed. “We never told our mother we actually didn’t go to church.” What the siblings found was a peaceful serenity that is rarer to find now with the amount of traffic and number of visitors to the canal.

Still there is something captivating about this modern marvel. “You drive along it and you have these incredible views and just think about the history of those who had to dig it. It fascinates me,” Smith said. “We don’t see this type of construction today. Just stop and think about what they had to work with and look at what they accomplished. The canal is an incredible piece of history dug by hand.

By Christopher Kazarian